Behind the Scenes: A Conversation about Art and Writing with Mahak Jain

Mahak Jain's short fiction and poetry have appeared in The Journey Prize Stories 28, PRISM international, The New Quarterly, Joyland, The Humber Literary Review, and Room. She is also the author of Maya, a picture book about fear, adventure and imagination, which was named one of CBC Books' Best Books of 2016. Set in India, Maya was illustrated by Owen Sound-based paper artist Elly Mackay. To communicate her vision for Maya, Jain created a Pinterest board for Mackay; they detailed their creative process in an Owlkids video that features some fascinating peeks at Mackay's studio. I caught up with Jain to ask her a bit more about this process, and about how she sees the relationship between the visual and the written in her work.

Andrea Bennett: Before you published Maya, if I've got the timeline correct, you were the managing editor at Owlkids. Had you worked with illustrators before, in your capacity as an editor? How did the process differ when it came to realizing the vision for your own book?

Mahak Jain: As Managing Editor, I didn't work directly with illustrators, but I did get to witness the start to finish journey of illustrating a picture book in-house. And that journey began even before the art started to come in, with the selection of the illustrator, a decision that profoundly determined the creative vision of a picture book.

In the past, I was able to overhear the behind-the-scenes conversations about the relationship between the art and text, how the negotiation between the two told a bigger story, what bigger story we were trying to tell. When working on my picture book, though, I was removed from that communication. A picture book is a strange thing and very different from working on, say, a novel. I wrote the words and Elly, the illustrator, did the art, but the publishing team (the editor and designer, especially) also shaped the book by bringing the art and the writing together. I wasn't even entirely aware what kind of book my story was going to become until the book was done; there was a sort of magic and synergy to the process.

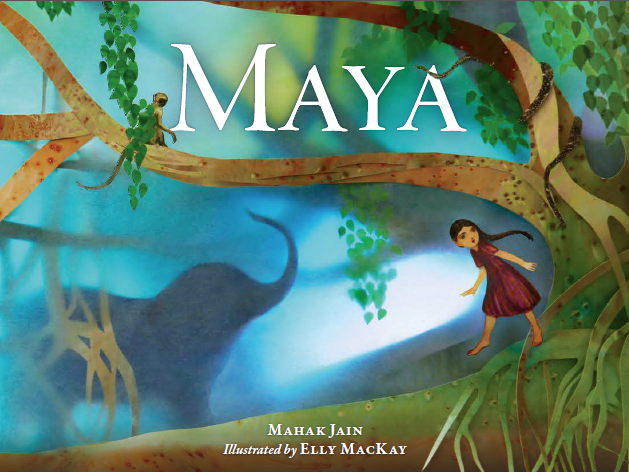

From the outside, it must seem bizarre that I never communicated with the illustrator; she was sent my manuscript and I assume some guidance from the editor and designer, but I don't know what shape or form that took. The only time I communicated with her was to answer some practical questions (what was the weather like?) and offer some reference photos via Pinterest; even this was considered an unusual amount of communication between an author and illustrator.

I wasn't particularly nervous about being so removed because I knew from working in children's publishing that the process works, and I trusted everyone involved. But I was still amazed when I saw the final book because Elly had, somehow, without needing anything explained to her, understood at a deep, inexplicable level what the book was about. And the publishing team had understood that she would be the artist who would understand my story. It really cemented for me that art is a very real, very deep form of communication that requires no foreword, appendix, or note to the reader.

AB: Are you a regular Pinterest user? Had you developed the board partially as a tool for yourself, as you worked on the story, or was it something you put together to guide the illustrations? Is Pinterest a tool you'll use again in the future?

MJ: I didn't use Pinterest before and created an account especially for Maya. I will use it again in the future, though. It's a really handy way of visualizing a world that exists primarily in text form. It reminds me of a writer I met some time back, who wrote in a room filled with images of faeries, which is what her books are about. I mean, filled with paintings, books, figurines; it was like stepping through a portal. I could see how it helped her slip into the world that she was writing about. I don't have a room like that to reconfigure, but a Pinterest board can offer that kind of space, a visual map.

AB: I like the idea of that—a visual map. In Maya, as Maya's mother is telling her a story about rain and the banyan tree, we can almost see Maya's thoughts come to life. (I'm thinking specifically about the moment where Maya exclaims, "It's a tiger!" as an autorickshaw growls past.) Do images drive you, as a writer? How do you envision the relationship between words and images in your work?

MJ: Images do drive me as a writer. Especially after writing Maya, and experiencing that play between images and text, which is inherent to a picture book, I started to understand that narrative is essentially wordless. Now I am much more attentive to the rhythm and movement and shape and peaks of the underlying narrative structure of a story. Because at some point words are not enough and there's something that needs to be expressed outside of language itself. The process is both imagistic and rhythmic. So when Maya's thoughts transform into an image, they transform into something experienced versus explained, which is how I think of narrative itself.

AB: Are there other tools that you use as a writer that you find helpful and would recommend to others?

MJ: I haven't used it too much, but Scrivener is a good one. It's not expensive—about $40—and yet it provides a very useful tool for organizing long works of any kind. The thing I love most about it is that you can put all your research (images, videos, links) into the same file as your project.