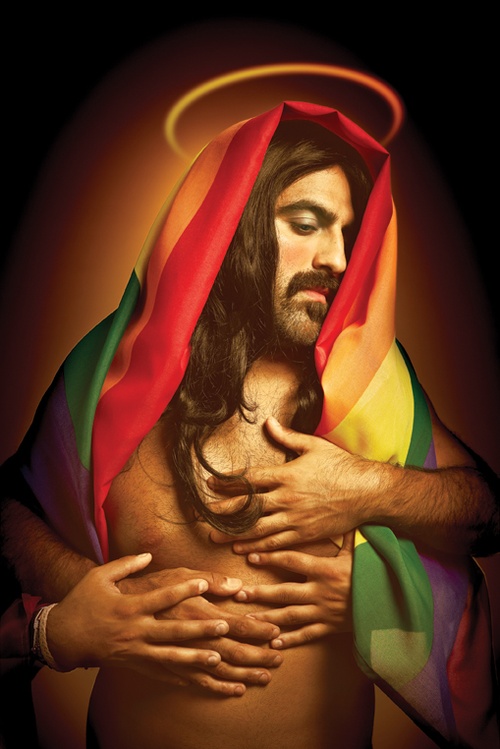

Gays for God

The religious right is the most powerful obstacle to LGBT equality in America. But a growing movement of gay evangelicals is challenging homophobia from within the faith.

Photograph by Kourosh Keshiri.

I decided to be gay in 1990, shortly after I started graduate school. I had just earned my BA from a Baptist university in Waco, Texas, and I wanted to try something different. My new best friend was named Robert; I understood that he had a little crush on me. Like me, Robert was a Christian—we were both studying the great Danish theologian and philosopher Søren Kierkegaard—but he didn’t have my evangelical education. One night, in a wild underground club in Austin, I resolved to kiss Robert on the dance floor. We were young and drunk and surrounded by beautiful men, and I thought, “Here’s my chance.” Many of my heroes were gay, such as Oscar Wilde and even Kierkegaard, probably. I had prayed about it; I had asked God to make me gay. So there, under the strobe lights, with Depeche Mode booming in the background, Robert and I kissed.

I felt nothing. Friendship and sincere affection, sure. Robert and I remained close. But I realized I couldn’t will myself to be gay, no matter how badly I wanted to be. It was out of my hands. God had created me straight, and no man—not even Robert—could unmake what God had made.

Over twenty years later, I’m married, have three daughters, chair a philosophy department and no longer know what to think about the existence of God. When I teach gay rights in my Contemporary Moral Issues class, my students constantly argue about Christianity and sexual orientation. Naturally, I’ve always known that Christian evangelicals in general, and Baptists in particular, are opposed to homosexuality. But even when I was a card-carrying Baptist, I’d believed in queer rights, and so did my professors and mentors. I understood homophobia as misguided politics and amateurish, biased textual interpretation. Until recently, it had never occurred to me what it would mean, in a personal sense, to think that God might be opposed to your sexual orientation.

Then I began to meet some new people: men and women who are fighting against the idea that one has to choose between being gay and being an active—even a conservative—evangelical Christian. They call themselves LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender) evangelicals. They are among the kindest, gentlest people I know. They are also among the most unwanted and unrecognized. But they are determined—and their numbers are growing.

If LGBT evangelism has a spiritual father, it is Ralph Blair, a suave seventy-three-year-old New York City psychotherapist with an almost entirely gay clientele. He started advocating for the rights of gay Christians in 1962, while a member of the Inter-Varsity Christian Fellowship at the University of Southern California. Two years later, after delivering a pro-gay talk at Yale, he was not reappointed to IVCF staff at the University of Pennsylvania. In 1975, he founded a group called Evangelicals Concerned, which, as far as I can tell, is probably the oldest queer evangelical organization in the world.

Blair has never had a problem reconciling his homosexuality with his faith; other evangelicals, he says, wouldn’t have a problem either if they took the gospel as seriously as they claim. “Long-term, monogamous gay relationships are completely compatible with New Testament teachings,” he told me as he prepared milky iced coffee in his office on the Upper East Side. “And I believe that the New Testament is the revealed word of God. I’ve felt an obligation, in my life, to help others understand that. Certainly, to help gay Christian evangelicals who feel they have to choose between their religion and their sexuality. But also, and perhaps more importantly, to reach out to the Christian evangelical movement as a whole in this country.”

Like other queer Christians, Blair and his fellow LGBT evangelicals believe that Jesus saves, and that marriage between same-sex couples should be legal. But as evangelicals, they take their faith a step further, dedicating their lives to converting LGBT nonbelievers, and reaching out to mainstream evangelicals who have been forced into the closet. They’re also also stricter in their faith than other Christians, emphasizing personal salvation and conversion, the literal truth of the Bible and the superiority of Christianity over all other faiths.

No firm statistics exist on how many LGBT evangelicals there are in America. Like the early Christians, who were actively repressed, most queer evangelicals practice their faith in small, private groups (usually in Bible studies in someone’s home), or, much less commonly, in openly gay-friendly churches. Their message is twofold. First, contrary to the claims of mainstream evangelicals, biblical scripture does not prohibit homosexuality. Second, a community of practicing LGBT evangelicals is out there, waiting to receive gay fellow believers.

Blair profoundly believes in his cause. The appeal of his approach is that he reads the Bible as an evangelical—strictly, even literally—but arrives at a different conclusion: that it is not a sin for a man to have sex with another man. The Old Testament passage most often cited as a prohibition against homosexuality—“Thou shalt not lie with mankind, as with womankind; it is abomination,” from Leviticus—is revised, according to Blair, by the love of Christ. Blair is not suggesting that we throw out the Old Testament, but he believes that Christians must reinterpret or reject passages that are clearly incompatible with Christ’s instruction to love one another as we love ourselves. In his First Letter to the Corinthians, Paul lists gay sex as a sin, but, as Blair points out, anal sex was considered a form of humiliation in Paul’s day—something one would do to a slave or an enemy. Paul was warning against violent and degrading acts, not loving ones between consenting partners.

But that interpretation puts Blair at odds with the mainstream evangelical movement—the most powerful anti-gay force in America. In a recent survey of over two thousand evangelical ministers and leaders in 166 countries, the Pew Center found that 84 percent of them think homosexuality should be discouraged. The teachings of three prominent American evangelists—Scott Lively, Caleb Lee Brundidge and Don Schmierer—inspired a Ugandan bill that initially imposed a death sentence for gay sex. Earlier this year, the high-profile televangelist Pat Robertson, who often condemns homosexuality, said that gayness is “related to demonic possession.”

The fight over gay rights has also gained a foothold in the 2012 presidential election, which most pundits predicted would turn upon Barack Obama’s handling of the economy. In May, Obama announced that he personally supports same-sex marriage; three months later, the Democratic Party’s platform committee endorsed marriage equality for the first time. Both of these decisions followed Obama’s December 2010 repeal of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell, a policy that forbade gays from serving openly in the military.

But opposition to LGBT rights has been even more vehement. Both Mitt Romney and his Republican running mate, Paul Ryan, oppose marriage equality. (Interestingly, though, neither is an evangelical Protestant. Romney is Mormon and Ryan is Catholic.) In May, one of Romney’s foreign-policy advisors stepped down after he was outed as gay. And this summer, Dan Cathy, the evangelical president of the fast-food chain Chick-Fil-A, spoke out against same-sex marriage, saying his company, which has reportedly donated millions of dollars to anti-gay groups, supports “the biblical definition of the family.” His remarks caused a heated controversy, with gay-marriage advocates staging “kiss-ins” outside Chick-Fil-A locations and their opponents organizing a “Chick-Fil-A Appreciation Day” in response. Although gay conservative groups like the Log Cabin Republicans and GOProud are trying to change Republicans’ minds on homosexuality, there’s no doubt that the party is still beholden to America’s right-wing evangelical movement.

As difficult as it is to imagine how Blair might make inroads into this world, he insists that he can. “Evangelicals only listen to other evangelicals,” he explained. “An ordinary gay Christian speaks and they just turn off their ears. But an evangelical Christian speaks and, even though he’s gay, they’ll give him a shot.”

It’s hard to be Christian and to evangelize. It’s considerably tougher to be gay and to “evangelize”—to spread the word that homosexuality is okay. But imagine having to spread the word both of Christ and of queerness. Because of the religious right’s hostility to homosexuality, gay evangelicals are generally disliked—or even openly despised—not just by straight Christians but by other gays, too. And the LGBT evangelical movement faces its own internal divisions, which threaten to undo all the progress it’s made. Queer evangelicals have the potential to cast homophobia out of the religious right and change the face of American politics—but only if they can keep their own movement alive against the odds.

Last summer, I traveled to Oakland, California for ConnECtion, the annual convention of Evangelicals Concerned Western Region. (At the time, Evangelicals Concerned was divided into two halves, the Eastern and the Western.) At the conference, there were prayer meetings, performances by contemporary Christian rock musicians and break-out sessions to teach people how to promote the LGBT evangelical message. There was also lots of “sharing” around the hotel bar. It wasn’t as overt as conference sex-talk sometimes is, but, as I chatted with various couples, they admitted to having first met at this conference or one like it. It occurred to me that it’s hard enough to meet a suitable partner in my own straight, agnostic shoes; it must be so much more difficult for a gay evangelical.

I met Eunice Coldman on a bench in the mezzanine of the Marriott Hotel, where she was counseling a shy, slender transgender man in blue jeans and a Western shirt. Coldman wore a nose stud, dreadlocks and turquoise earrings. She was discussing “the radical inclusivity of Jesus Christ.”

“Jesus wants us all,” she said, flashing an enormous, winning smile. “That’s the heart of his whole teaching. I don’t care if you’re practicing voodoo. If I don’t try to understand what you believe and where you’re coming from, how can I hope to talk to you? How can I expect you to hear what I’m saying?”

The young man nodded. “That’s why I’m here,” he said. “It’s a place where I feel safe. Where I fit in. Where I belong.”

Coldman’s message is a departure from the traditional stance of Christian evangelicals, and her presence at the conference—she was newly confirmed for a position on the ECWR board of directors—was a direct challenge to Blair. The crucial difference between their philosophies lies in the question at the heart of all Christian evangelism, gay or straight: what does it really mean to be an evangelical? For Blair, it is the acceptance of the “evangel”—the good news that Christ is God—and the obligation to spread the word of that news. For Coldman, it is the more general idea that anyone can be a Christian, regardless of sexual orientation, gender or race. According to Blair, this represents the introduction of relativism to the evangelical message, threatening its purity and therefore its very Christianity.

Even the fact that Coldman is a woman was considered a provocation. Women, it seemed, did the vast majority of the work at ConnECtion; every time I sat in the large conference room where most of the talks and prayer circles were held, it was women moving chairs, hanging whiteboards for workshops or manning the registration tables. And there were probably six men for every woman in attendance. It’s hard to escape the thought that the “G” in LGBT is what mattered most here. This also reflects a long-running tension in gay-rights activism; many lesbians, transgender people and queers of colour have historically felt sidelined by white gay men.

One day, in the conference room, a boyish, elfin man fawningly introduced Blair, who was slated for a speech. “Ralph is not just the pioneer of LGBT Christian evangelism,” the man said, holding his hands out toward Blair, who sat at the back of the crowded room. “He is its prophet.” The atmosphere had that odd electricity and breathlessness you get in a church or concert or football game. The attendees were dressed casually, but their clothes looked deliberately chosen, as though they’d arrived for a party. In a brown button-down shirt, khaki pants and handsome glasses, his blue eyes flashing, Blair stepped up to the podium.

He got right to the point, launching into an attack on Coldman. For Blair, “radical inclusion” is wrong because it is relativistic, and ignores the fundamental incompatibilities between the world’s religions. It is also “a strategic blunder,” because traditional evangelicals only take their queer counterparts seriously when they hold true to the gospel. And it constitutes “an abandonment of devotion to Christ.” For these reasons, Blair said, his voice rising in religious fervour, Coldman “must be removed from the board.”

Stunned silence. Coldman left the room.

I caught her outside, about fifteen minutes after the speech, in a hallway near the hotel bar. She took a deep breath, her fingers fluttering. “He’s making the same arguments they always make,” Coldman explained. “This is the same argument the straight folks are using for keeping LGBTs out of the church. Most of America thinks Christian evangelism, they think of intolerance. And we just heard it. Why do you think most gay folk reject their religion? Arguments like you just heard from Ralph Blair.”

In a brewpub, under the dappled shade of grapevines, I spoke with Justin Lee, the thirty-five-year-old founder and executive director of the Gay Christian Network. GCN has nearly twenty-two thousand subscribed members, up from just eighteen a decade ago. The group’s function is to provide a safe online gathering place for gay evangelicals: to help them coordinate with one another, to run conferences, to bring in other queer groups like the Evangelical Network—which Blair describes as a “more conservative, Pentecostal, countrified” set—and to produce educational materials that can be used in prayer groups and “open-to-gay” evangelical churches.

Lee has alopecia, and his gentle, eyebrow-less face, pale skin and oval head give him a saintly quality. He has no formal training, and he founded GCN more or less by accident after he graduated from Wake Forest University in 2000 and started blogging about his attempts to square his religious beliefs—“I never doubted that I was a true Christian evangelical”—with the fact that he was sexually attracted to men. Soon, others with similar predicaments began contacting him, and GCN became a full-time job. He lives in evangelical country: Raleigh, North Carolina.

“There are lots of gay Christian churches in the country,” Lee explained to me. “And that’s a good thing. We are a movement. We are a place evangelicals can come to learn about why gay is okay in the eyes of Christ. We answer questions and spread information. That’s our role as Christian evangelists.”

Lee’s line is softer than Blair’s: he includes both “A” gay Christians—queer evangelicals in committed, long-term relationships—and “B” gays—queers who accept a lifetime of celibacy as a consequence of their Christianity. Lee is an A gay, but he recognizes that some gay evangelicals still believe that the Bible prohibits homosexuality, and he doesn’t want to exclude them. Blair, by contrast, is a hard A-man—he thinks all gays should accept their sexuality. But both agree that their movement is making some progress among mainstream evangelicals.

Indeed, there are encouraging signs. Last year, representing the powerful evangelical coalition Faith in America, Dr. Jack McKinney, who is straight, presented a ten-thousand-signature petition to the Southern Baptist Convention, calling for it to “stop misusing the Bible to promote religion-based bigotry” and “perpetuating abuse against gay people.” The Southern Baptist Convention is arguably the most staunchly homophobic branch of the evangelical movement, so it’s hardly surprising that it did not endorse the petition. But the fact that McKinney, on behalf of thousands of ministers and followers, was calling the Southern Baptist Convention to account—from within the evangelical tradition—was a landmark.

“The saddest thing,” Lee told me, his expression earnest, “is that if there’s one thing you ought to associate with Christian evangelism, it’s love. But instead, the traditional evangelical establishment has turned everything on its head. We’re viewed as intolerant, unkind, even hateful. That’s the real tragedy of Christian evangelism in this country today.”

One of the ugliest faces of that intolerance is the so-called “ex-gay” movement, spearheaded by Exodus International, a group tacitly endorsed by mainstream evangelicals. Exodus claims that “Christ offers a healing alternative to those with homosexual tendencies” and offers LGBT Christians the “freedom to grow into heterosexuality.” Its mission is exactly the opposite of that of groups like Evangelicals Concerned: Exodus wants to convince gays that, through Christ, they can become straight. Exodus even holds an annual “Freedom Conference” to teach attendees—pastors, therapists, young gay people who come with their parents—how Christ can change a person’s sexual orientation.

In an effort to learn more about the ex-gay movement, I tracked down a man named Daniel at ConnECtion. Daniel is from San Francisco, and he is a teacher and self-described “victim” of an ex-gay ministry that pre-dated Exodus. He was immediately disarming and open; in fact, none of the evangelical gays and lesbians I met had that intimidating, off-putting quality unique to the deeply religious.

“I thought I had taken care of my ex-gay stuff with gay-affirmative counseling until I was in that room praying half an hour ago, and then I started having flashbacks,” he told me. “‘I’m a failure.’ ‘Christ doesn’t love me.’ ‘Christ won’t change me.’ That ex-gay kid inside who suffered so much just won’t listen to what my rational mind knows. But I get in there and suddenly it all comes out, and I remember that God wants me to be gay. And that scared ex-gay kid inside of me was listening.”

Daniel started to tear up, and I had a small glimpse into what that must have felt like: to be told that God Himself wants you to be someone else. Your parents, your friends, your pastor—everyone you love and respect—are all praying for you to completely alter who you are, and Jesus is cheering them on. You stay the same, but you feel guiltier and guiltier, dirtier and dirtier.

“Then I meet with other gay evangelicals and I realize, no, I don’t have to choose between my faith and my sexuality,” Daniel said. “I’m not ashamed. We believe in Christ and in spreading Christ’s word. And we are uniquely suited to do that, because we are gay. Because there is a huge group of Christ’s children out there who have rejected Him because they think they can’t believe in the evangelical faith of their upbringing. But they can. Jesus wants them back. God wants them back.”

“You can’t have it both ways,” Ralph Blair told me. “Either Christ is our Lord and Saviour and all other religions are wrong, or he’s not. I’m a Christian evangelist. I believe Christ is our Lord and Saviour.”

Blair possesses a zealotry about him that most other queer evangelicals do not. I wonder if all his years of dealing with the inflexibility of the mainstream evangelical movement have affected his way of seeing the world. To me, Eunice Coldman has the right language for the difference between Blair’s approach and her own: her style is inclusive, and his is exclusive. It’s hard to reconcile that exclusivity with the real-life problems of gay evangelicals today.

It would be too much to say that Blair has lost touch with his own movement. But he is a hard-liner, uncompromising, and I suspect that the future of LGBT evangelism will be more open than his particular brand allows. The more I spoke with members of the movement, the more I wondered why the label “evangelical” even matters. For Blair, it’s crucial, because it defines a set of very strict interpretations of the gospel; for Coldman, “evangelical” seems to mean “spreading the word,” and does not carry a lot of doctrinal weight.

As it turns out, Coldman won the battle: ECWR has since dissolved, and its membership has joined Justin Lee’s Gay Christian Network. Both Lee and Blair are pleased with the outcome and remain friends. Anyway, there are larger battles to fight. Lee’s forthcoming book, Torn: Rescuing the Gospel from the Gays-vs.-Christians Debate, argues that there’s a common misconception that gays and Christians are enemies, on opposite sides of a culture war. The truth, he says, is that a lot of people are somewhere in the middle. The book tells the stories of people who feel torn—compassionate pastors, Christian parents of gay children, and queer Christians themselves—and shows why the gays-vs.-Christians myth must be banished for the sake of people on both sides.

For Blair, at the end of the day, the movement is about theological truth. But for people like Lee and Coldman, it’s also about the day-to-day reality of being gay and Christian. Ultimately, it doesn’t really matter how many little schisms might occur within LGBT evangelical groups, or even if queer evangelism becomes—as Blair fears—just plain old queer Christianity. Whichever arguments you rely on—as with all biblical exegesis, the theological debate will surely go on endlessly—both Blair and Coldman can genuinely help other queer believers hold on to both their faith and their sexuality. I still don’t know whether God exists, whether He makes us who we are. But I do know that there are a lot of people who believe in Him, and who believe that He watches over them, no matter whom they love.