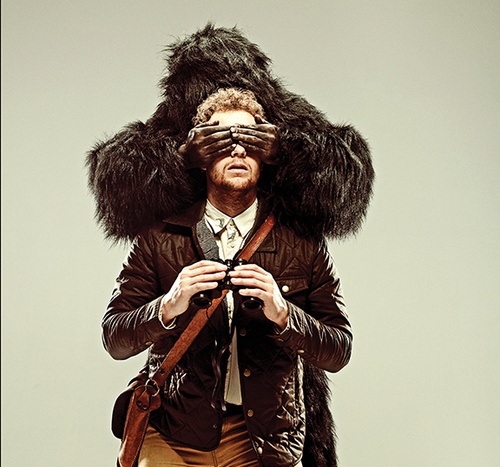

Photograph by Sylvain Dumais.

Photograph by Sylvain Dumais.

On the Trail of Ignored Beasts

Cryptozoologists head into the forest looking for something bigger than themselves.

THOMAS STEENBURG went into the British Columbia wilderness in April 1986, and he didn’t come out again until Halloween. He was twenty-five years old and had just left the Canadian army after eight years stationed in Victoria and Calgary. He had several months’ leave at his disposal and he was going to look for Sasquatch.

One day in early summer, he was searching for prints in the soft dirt shoulder of an unpaved forest service road northeast of Whistler. As he scanned the ground for signs of the Sasquatch, he heard a noise. Suddenly, something huge was charging at him, “like a freight train.” He started shimmying up a cluster of young, thin trees, but claws grabbed him by the backpack and dragged him toward the ground. “For whatever reason, she let go, and I climbed right back up those trees,” Steenburg says. Turning his head, Steenburg saw that the creature was no Sasquatch, but a grizzly bear. The bear shuffled and huffed around the base of the trees before lumbering back towards deeper forest. Steenburg’s backpack was shredded, and two of the bear’s claws had left puncture wounds in his lower back—he still has the scars today.

He was shaken, but Steenburg wasn’t ready to abandon the hunt. A few weeks later, an American couple said they’d seen something pace through their camp on the north bank of the Chehallis River. Steenburg went to the site near Chilliwack, found his first Sasquatch tracks and never looked back. “That sealed my fate,” he says. “If it wasn’t for that find in 1986, I might have given up on the Sasquatch mystery and gone on to what my ex-wife used to call ‘more important things.’”

Today, Steenburg wears round, wire-rimmed glasses and an over-sized khaki fishing vest with dozens of pockets. He drives a conifer-green SUV with “Sasquatch Research” and his phone number printed in big, white letters on the side. Steenburg runs a one-man cryptozoology operation; he’s a kind of freelance ’squatcher-at-large. In Harrison Hot Springs, British Columbia—the unofficial capital of Sasquatch country—he is known as the man to call if you see anything strange in the woods. “Hopefully they find me instead of one of the nuts,” Steenburg says, speaking around a pipe hanging out of one side of his mouth.

Broken down into its component Greek parts, cryptozoology means “the study of hidden animals.” Hinted at by folklore, legend and eye-witness accounts, the subjects of cryptozoologists’ dogged pursuit are creatures not proven to exist. (“Not yet proven,” cryptozoologists hasten to add.) Famous examples of these unknown animals—called cryptids—include the elusive, white-haired Yeti of the Himalayas (aka the Abominable Snowman); the long, rippling Canadian lake serpent Ogopogo; the spiny, goat-sucking reptile Chupacabra of the Americas; and, of course, perhaps best-known, the hairy bipedal hominid Bigfoot, called Sasquatch in Canada.

The study of cryptozoology is still young enough—and fringe enough—that to even call it a field is controversial. There’s no governing body monitoring the practice, you can’t earn a degree in it and, except in rare cases of oddball private patronage, no one will pay you to do it. The only requirement for being a cryptozoologist is to call yourself one. As a hobby, it’s hunkered down where science and not-quite-science meet, attracting its share of the out-there.

When modern cryptozoology emerged in the mid-twentieth century, its proponents kept up a tone of academic seriousness and there remains a movement among some cryptozoologists towards rigorous application of scientific methodology. These researchers want their work to be appreciated as a valid offshoot of orthodox zoology, rather than a pursuit of the paranormal. Convinced there are creatures roaming woods and waters that still haven’t found a place on the officially sanctioned species list, these self-described investigators hunt for evidence, hoping to find the definitive proof that will earn their cryptid—and maybe themselves—a place in mainstream science.

IN 1962, philosopher Thomas Kuhn coined the term “paradigm shift” to explain how science moves forward in fits of upheaval, repeatedly razing and rebuilding assumptions. In the lulls between scientific revolutions, evidence that contradicts the way we see the world is either missed entirely, or written off as an inconsequential anomaly. But as out-lying evidence mounts and reaches a critical mass, what we hold as scientific truth must eventually be overhauled. Paradigms that gain traction— the Copernican cosmos, quantum mechanics and Einstein’s relativity, to name a few—cause whole-scale turnovers in how we think, forcing normative and radical world-views to swap places. Once the paradigm shifts, we can never go back to seeing things as we once did. While early adopters of soon-to-prevail paradigms will later be validated as harbingers of reason, they invariably start out looking like crackpots. And not every paradigm will shift. Many theories from the fringes of science never garner enough evidence to crawl their way into favour. But that doesn’t stop many believers from trying.

The first definitive piece of cryptozoological literature—a more than 600-page tome published in 1955 by a Belgian-French zoologist who went crypto—was called, in its original French, Sur la piste des bêtes ignorées. Literally translated: on the trail of ignored beasts. Cryptozoology has always hinted at the loneliness that comes from looking where no one else is, listening in the bush for the rustle of something cast aside and following where it may lead. Cryptozoology offers the hope that, somewhere beyond the beaten trail, every ignored beast has a path.

THERE MIGHT BE NO BETTER PLACE on earth to stage a game of inter-species hide-and-seek than here in Canada, with its landscape of millennia-old trees and ocean-sized lakes. Canada has one of the lowest population densities of any industrialized country; only 3.7 people per square kilometre. When it comes to Man vs. Nature, the odds aren’t in our favour. Least of all in British Columbia, where nature has the upper hand in both size and diversity, scape-shifting from rainforest to mountain to desert to ocean. Everything here is oversized and surreal, possessing the kind of beauty that saturates as much as delights the senses, that seems to veer towards the sublime, the too-much. Even without the embellishment of undiscovered creatures, British Columbia’s natural spaces are Sendakian. This is where the wild things are.

The British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club is coming up on its quarter-century anniversary. It was founded in 1989 by current president John Kirk, the late James Clark, and Dr. Paul Leblond, a now-retired professor from the Department of Earth and Ocean Atmospheric Sciences at the University of British Columbia. The BCSCC’s mission is to support the study of cryptozoology with a scientific bent. To this end, they conduct field research, maintain archives and do education and outreach. They believe they’ve identified dozens of cryptids in BC alone, and they support field work abroad. The BCSCC is arguably the only contemporary cryptozoology organization that defines itself by its relationship to science. These days, the field is largely populated by ardent, cryptid-specific groups with chaotic websites and fractious online message boards. (For example, on “The Bigfoot Forums” a recent thread, entitled “Messages from Uncle Hairy,” discusses a member’s psychic communion with Sasquatch before the conversation devolves into in-fighting and a moderator intervenes.) The BCSCC makes every effort to distinguish themselves, trying to wield the tools offered by science in their amateur investigations. While the BCSCC members might believe in cryptids, they self-identify as skeptics.

“Time-keeping is the last thing a Sasquatch investigator is capable of doing,” Kirk declares. Things aren’t going as planned at the Club’s annual barbecue. A rogue bear was sighted at their usual venue in Sasquatch Provincial Park, so the BCSCC has settled for a manicured patch of grass at an RV park closer to town. Worse, the guy who’s supposed to bring the meat has gone AWOL. Finally, Bill Miller pulls up in an open-air UTV—normally used to ferry passengers to Sasquatch-sighting locations as part of the adventure-tourism company he runs with Steenburg—and a cooler of hamburgers, hot dogs, and sausages is carried from the trailer in back. The club’s VP and webmaster fires up a portable grill, and the de facto annual general meeting of cryptozoologists kicks off.

Once a year, the BCSCC’s membership is invited to get together at Harrison Lake to discuss the latest in their field: new research, promising sightings, tricks of the trade. Members come every year, Kirk says, because cryptozoologists are more than just dedicated: “They’re like addicts. They’ve got to get their fix.” Kirk has a voice uncannily like Alan Rickman’s, with the same half-muffled authority, like someone expounding on a dialectic with a blanket over his head. Dressed in camo flood pants and a sleeveless black T-shirt, with clip-on shades on his sunglasses and a Liverpool FC baseball cap over his long, dark-brown hair, Kirk looks like he’s been cast in a Harry Potter spinoff where Professor Snape cuts loose and goes on vacation. I ask Kirk how much time he devotes to cryptozoology. “Too much, eh?” he asks his wife beside him. Between staying up-to-date on the literature, writing his own articles, and handling the club’s newsletter, he says it’s about five hours. A week? I ask. No, he says, a day. Not counting time in the field.

On shows like the Discovery Channel’s Finding Bigfoot, investigators thrash and bellow their way through the woods, always just barely missing a cryptid encounter. It’s Sasquatch cast as a more dangerous Polkaroo. For serious researchers, the reality is far more mundane: drive into the backcountry or to the site of an alleged sighting, and very carefully pick over trees, mud, bushes, and logs. The aim isn’t to encounter the creature face-to-face, but rather to find physical evidence of its presence: footprints, hair, tissue, Sasquatch scat. “On TV you see these bigfoot guys go tramping through the bush at high speeds. What are you going to find that way?” Kirk asks. “You’ve got to work like a forensic identification technician.” Kirk might spend a whole day combing a small patch of woods; interesting finds might come only once or twice in a lifetime.

The BCSCC members show me plaster casts of famous Sasquatch footprints. These aren’t originals; they’re second and third generation, casts of casts of casts, but still, there’s something unnerving about them. These could very easily be the work of hoaxers, but they’re certainly not bear prints, or random squelches in the mud, or anything else from nature as we know it. They look like human footprints, but much, much bigger. And there are details. On one, it looks like the front of the foot has pressed down and gripped the mud, the earth rising under and between the toes before whatever it was pushed off and walked away.

Some of the better-known cryptids the BCSCC covers don’t leave footprints. They’re water-bound; Ogopogo, the huge, lean lake serpent of the Okanagan, and Cadborosaurus Willsi, an ocean-dwelling creature said to inhabit British Columbia’s coastal waters. In Victoria, BCSCC members run a surveillance operation called Caddy-Scan: a CCTV camera recording the waves over Cadboro Bay, hoping to spot something more. The camera’s been running for fourteen years. No luck yet.

Cryptozoologists go searching in their spare time, not as a job. Many BCSCC members believe that if they were able to get out more often, they’d have greater success. And they’d be happy to. After all, “A bad day of ‘squatchin’ is better than a good day of work.” But this is no easy-going hobby. The places cryptids might turn up are wild and isolated, and investigators must beware of all kinds of dangers: wildlife, harsh geography, even grow-ops with their booby traps. “It is wilderness, and it’s not for the timid,” Steenburg says, recalling his grizzly encounter. “There is a chance that you will run into something that may want to eat you.” Most go into the woods armed with emergency supplies, navigational tools and often guns. And of course, no ‘squatcher is without recording technology in case they actually find something: surveillance equipment, audio recorders, top-of-the-line cameras.

Cryptozoology’s not cheap. BCSCC VP Adam McGirr estimates he’s invested a good ten grand, and he hasn’t been at it for as long as some. By day, McGirr works as a technical writer for BC Housing, where, he says, he’s “out of the closet” as a cryptozoologist. His work with the BCSCC, however, is his “dream job.” On the weekends, when it’s nice out, he’ll sometimes set up a booth in Vancouver’s Stanley Park and, armed with literature, he’ll chat with interested passersby.

McGirr barbecues non-stop while we talk. Two boxes of cookies go unopened, and even the chips are barely touched: everyone here is hungry for meat. John Kirk jams a wrinkled hot dog into a bun alongside a hamburger patty and enjoys the meat-on-meat mash-up. “The ultimate carnivore’s meal,” he affirms between bites. It’s generally thought that Sasquatch is omnivorous—it’s likely the only way it could get enough calories to stay alive. (Skeptics say there’s simply not enough space in the food chain for a caloric vacuum Sasquatch’s size.) Though the group theorizes about the cryptid’s behavior based on eyewitness accounts, Kirk is quick to emphasize that nothing about Sasquatch can be counted as certain. “There is no such thing as a Sasquatch expert,” he says. “Everything is hypothetical.”

The definition of a cryptid can be as difficult to grasp as the creatures themselves. Modern cryptozoologists disagree about what is worth pursuing at all. Do animals that are reported far beyond the reaches of their known habitat count? What about mythical creatures that no one (or next to no one) reports seeing, like unicorns, centaurs, or mermaids? Tug at the edges, and “cryptid” could be opened up to include werewolves, aliens, even ghosts. For those trying to gain legitimacy in scientific circles, this kind of thing is deadly. All it takes is one blog post explaining the relationship between Sasquatch and extra-terrestrials (and there isn’t just one—there are many) or one pseudo-scientific paper that claims to have mapped the Sasquatch genome and found the DNA of angels (which happened in Texas just this year) and a big, fat brush comes down and paints all cryptozoologists the same shade of crazy.

NOT EVERYONE WHO GETS into cryptids is a lifer. Michael Woodley, a British evolutionary psychologist, became interested in the field several years ago as a graduate student. For academics, territory not already mauled by other researchers is a scarce resource, and Woodley felt cryptozoology was full of opportunities to do new, novel science. After a flurry of academic output, however, he dropped it. “Essentially cryptozoology is not science,” he says now. “I exhausted the possible space of all scientific developments, shall we say.” When he was still at it, Woodley published several academic papers in peer-reviewed journals, and a book about sea serpent classifications. In one paper, Woodley proposed a new nomenclature for describing cryptids using a modification of mainstream zoological classification. In another, he looked at a Cadborosaurus case study by Edward Bousfield and BCSCC founder Dr. Paul Leblond and used a ranked index of characteristics to show that what they were touting as a baby Cadborosaurus was, in fact, a pike fish. To Woodley, the point was to do good science. He thought that was what cryptozoologists would want, too, but not everyone shared his ambitions. “It’s not true of all cryptozoologists, but there’s a hardcore there that would be very resistant to the de-amateurization of the field,” he says. He sees a fundamental conflict they can’t seem to get over: “There is an irony, an irreducible pluralism, between these objectives of cryptozoology: to obtain some kind of mainstream credibility on the one hand, whilst on the other hand there’s this large following who are non-technical in orientation and who don’t really want their mysteries to be taken away from them.”

If a Sasquatch was found, the cryptid would upgrade to animal, and the whole operation would drop the crypto- and find itself squarely in zoology. But where would that leave the amateur ‘squatchers? “If and when—this is a big if and a big when—a specimen is obtained, guess what they’re going to do?” asks Kirk. “They’re going to come in and say ‘Okay, get out of the way now.’ No. You’re not getting in the way.” “They” are the scientists, the pros, the Man. Though he can’t name names, he says the BCSCC has made contacts at major Canadian universities who are prepared to include them in the research if they bring in a specimen. “We have it all set up,” he says. “The protocols are in place for us to say, ‘Okay, here it is, let’s go.’”

Just talking about what might happen if a Sasquatch was actually discovered—the thing he’s been working towards for half of his life—Kirk sounds nearly panicked. “Stuff science!” he says, as close to yelling as I’ll ever hear him. “Where were they when we, the amateurs, were spending our own time and money doing this? And here are these Johnny-Come-Latelies taking the ball and running with it. The ball belongs to us. That is a fact.” Brian Regal, a science historian at Keane University in New Jersey who studies the tug-of-war between amateurs and scientists in the hunt for cryptids, says the only advantage Kirk and his like have comes from being ignored. Science thinks there’s nothing there to find, but if they were proven wrong, they wouldn’t waste time choking down their humble pie. “If it was found to be real, the mainstream scientific community would move in and take over,” Regal says. “You could still be an amateur and go around the woods and take pictures and things, but as far as real research is concerned, that would be out of [amateur ‘squatchers’] hands. Very few of them have the kind of training you need to do it.”

Michael Woodley’s post-cryptid focus, on the development of human intelligence over generations, has taught him something about his one-time interest: he says both the desire to be tantalized by mystery, and faith in our beliefs in spite of evidence to the contrary, are hard-wired in the human brain. “People have these heuristics at their disposal, these biases of processing and reason which make them want to see monsters, which make them want to think that the world is a more fantastical, surreal place than is actually the case. To take that away and replace it with a sterile, cold, fact-driven scientific model of reality is something that is deeply disconcerting.” Tallying up the amateurs’ batting record is hard, because it depends on who you ask. Cryptozoologists have their wins: totally, definitively-real species like the okapi, the bondegezou, and even the mountain gorilla, all of which have crossed over from folklore to reality. Once considered so far-flung into myth territory that it was called the “African unicorn,” the okapi—an improbable-looking ruddy, stubby giraffe with zebra legs—is widely considered cyrptozoology’s biggest get. Its existence was confirmed by amateurs in 1901.

But you don’t have to be a cryptozoologist to find new animals. Scientists practice what amounts to cryptozoology all the time, hunting for new species based on ancient and contemporary local accounts. In academic circles, this is called practicing ethno-zoology rather than goin’ ‘squatchin’, but the idea is the same: follow a story into the woods hoping to emerge with something new. The difference, some will tell you, is that modern cryptozoologists have whiffed at most, if not every, ball they’ve been thrown. But they never stop coming up to bat. This persistence is one of the things that discredits them. No cryptid is ever dropped entirely. There is always someone, somewhere still on the case.

JUST A FEW DAYS BEFORE the barbecue, two new Sasquatch videos surfaced from Mission, B.C. The first records a group of Chinese tourists crowding the side of the road, photographing something unidentifiably ape-like not far into the woods. The second shows a dark, upright creature strolling casually along a ridge near a logging road. The shot’s not close enough to be able to say how big the creature is, or how much it might resemble a man in a gorilla suit. The BCSCC encounters a lot of hoaxes, and they don’t have high hopes about the validity of the Mission videos. The biggest red flag: though the videos were allegedly taken by anonymous sources, they’ve been brought forward by the creators of “Legend Trackers,” a site-specific smartphone app for virtual reality cryptid-hunting in real places. Though most hoaxers are just looking for attention or fame, the stink of profit-grubbing tends to diminish the field’s credibility. “When you’ve been in this business a while, you develop a good dose of common sense,” Steenburg says. The BCSCC has heard rumours that Mission is planning to rebrand itself as “the gateway to Sasquatch country” in an effort to draw tourists. The same thing has happened where we’re camped out today: for many years, Harrison Hot Springs tried to disassociate itself from the embarrassing Sasquatch connection, but last year, the municipal government and the Sts’ailes First Nations revived Sasquatch Days, a celebration of local culture that hadn’t taken place since 1938. (The word Sasquatch is in fact an anglicization of the Sts’ailes word for “wild man.”) The event is now shaping up to be an annual thing. The village has found that there’s an economic upside to embracing their monsters.

On the one hand, the BCSCC is happy to see cryptids enter the popular imagination; on the other, anything that draws cryptozoology closer to entertainment and further from science is worrisome. Same goes for popular TV shows like Monster Quest and Finding Bigfoot. They know the stars of these shows and like them well enough, but they also think they’re sell-outs. “Those guys can’t walk fifty feet without Bigfoot patting them on the butt,” an American ’squatcher with an absurd amount of surveillance equipment says. They laugh about it, putting on southern accents and doing impressions of the show’s more extreme moments, but it also seems to depress them. Some of the members of the BCSCC have known each other for over twenty years. They’ve seen the old guard of investigators die off, all without seeing the mystery solved. The grandfather of all things Sasquatch, John Green, is the last of that generation still standing. “He’s the A-1, number one guy,” Kirk says. He lives not far from where we’re sitting. At eighty-six, he didn’t make it out today, though the group says he still gets out in the field.

Many long-time ’squatchers sacrifice more than just time and money. “Cryptozoology has resulted in many divorces,” John Kirk admits. The group talks about René Dahinden, a contemporary of John Green’s who famously abandoned his family for what he called “the big, hairy bastard.” He spent a lifetime looking, and never saw the beast. (Canadians might remember Dahinden, with his deadpan delivery and thick Swiss accent, as the star of several Kokanee beer commercials in the ‘90s.)

At the BCSCC barbecue, there are just two women: the fiancée of a man with large Sasquatch tattoos on his arms, and Paula Kirk, John’s wife. Paula has been on the cryptozoology scene since the early ‘90s, but sees herself as more of an enthusiast than a researcher. She estimates that the community is more than 90 percent men. Kirk has been told she’s a “reverse skeptic”: someone who believes everything is true until proven false. The way she sees it, she isn’t looking to find magic, she’s just open to it. “You just have to be awake, alert to the idea that you might see something,” she explains. “I see a bald eagle almost every day. Now, why do I see one? Because I’m looking up in the sky.” And why should looking bother anyone?

To the non-believer, cryptozoology field research might seem like nothing more than eccentrically motivated camping trips. Where’s the harm in searching for something, whether or not it’s really there? The harm is that cryptozoologists are not the only ones with a vested interest in seeing mainstream science proven wrong. There are many not-quite and even far-from sciences jonesing for credibility, attention and money. Cryptozoologists are often counted among warriors against academic science and its stranglehold on truth, held up as an example of championing the personal freedom to believe whatever you want, evidence (or a lack of it) notwithstanding. Setting science up as a bastion in want of a good storming puts cryptozoologists in the same camp as creationists, and the two are not just hypothetical bedfellows; there’s a bid on the part of creationists to co-opt the pursuit of certain cryptids, believing their existence to be the thread-pull that will unravel Darwinian evolution. Mokele Mbembe—an alleged sauropoda or “long-necked” dinosaur living deep in the Congo Basin—has particularly caught the eye of fundamentalists, who mistakenly believe that a modern dinosaur co-existing with humans would corroborate a literal interpretation of Genesis. Most expeditions to the Congo in search of Mokele Mbembe have been executed and funded by Young Earth creationists, and many of these so-called scientific excursions have doubled as missionary trips.

Daniel Loxton knows cryptozoology can act as a slippery slope to more insidious ways of resisting science, but the question of whether it’s ultimately harmful is one he struggles with. An editor at Junior Skeptic magazine and co-author of a book that examines cryptid case studies from a historical perspective, he makes a living at debunking. But he stills sees a lot of good in cryptozoology. As far as he’s concerned, the complicated mess of wheels and pulleys behind the curtain is just as entertaining as the illusion. He really loves cryptids—he just happens to know they aren’t real. “It’s easy for me to see cryptozoology as a gateway drug to good science,” Loxton says. “There’s like seven billion of us: we can afford to have a few people who flail around on the fringes. Every once in a while they discover something really interesting.”

SUBSCRIBING TO A PARADIGM is like putting the world through Auto-Tune: flick the switch, and the discordant, random universe suddenly chimes together, falling into harmony with itself. A paradigm won’t drag an erroneous note all the way across the scale—it will just nudge it into place, make it fit in with what you’re already hearing. In the key of a paradigm, the world makes more sense. It becomes hard to imagine how anyone could hear things differently. Cryptozoologists hope, and believe, that their work will one day be validated as the cutting edge of science. But it may offer a glimpse into the past rather than the future. Cryptozoology recalls an age of the scientist as intrepid explorer, when heading off into the field meant travelling great distances into uncharted territory, investing your money and risking your safety in the pursuit of the unknown. It was a time when more remained untouched. When you peered into the woods, you might see something no one else had seen before. You just had to be brave enough to look. To cryptozoologists, it feels as though evidence is mounting in the case for the world they see.

Being a cryptozoologist is like living with the feeling of something in your peripheral vision, the feeling of a word that’s always on the tip of your tongue. “I think that we’re accelerating towards a critical mass, ” John Kirk says, “We’re heading towards a resolution.” The accumulation of sightings, sound recordings, blurry videos and tracks might seem like it is all building towards an end, but it isn’t. It can’t. No quantity of suggestive evidence—no matter how intriguing—will ever prove cryptozoologists right. In the case of Sasquatch, the only thing that will is a body: a hairy, seven-foot-plus, four-hundred-pound body that stinks like a skunk carcass, screams like a barrel-chested banshee and walks upright like a human. If and when that body is found, all the near-finds and almost-evidence that came before it will be blown away.

If Sasquatch is real, and the BCSCC comes across a live one, what happens then? Some take the utilitarian approach that shooting to kill will ultimately protect the creature by allowing it to be treated as rare wildlife. Besides, having a body (specifically the head. “You have to remove the head from the carcass,” Kirk says, “because it’s got the brain.”) is the only way for cryptozoologists to truly vindicate themselves. But the BCSCC holds fast to the belief that killing even one is unethical, no matter how much they want for proof. At the barbecue, guests and club members try to steer clear of talking about what they might use their guns for, but it still creeps into the edges of the conversation. It’s like being at a family reunion where all’s well until you bring up politics. “You go in with boom sticks, you’d better bring lots of rounds,” a huge man who looks a bit like a cartoon version of a Sasquatch says. “You kill one, there’s more that’s going to be coming for you.”

For Kirk, the issue comes down to how closely Sasquatch is related to us. Kirk has a background in law enforcement, and he says killing a Sasquatch would be homicide: “My belief is that they are genus Homo, and if they are genus Homo, you cannot kill one. You cannot kill a fellow human, no matter how primitive or backwards.” The pro-kill camp thinks that, as the feebler member of the genus, they could claim self-defence. Kirk warns that if any of them finds himself on trial for Sasquatch murder, they’ve left an online trail betraying their intent to kill. In such a case, Kirk would not stand behind the shooter.

I leave the barbecue with the Kirks, and we follow the winding highway out of Harrison Hot Springs, driving away from the mountains and back towards the suburbs of Vancouver. The sun hangs late in the sky, lingering over that long summer hour that makes everything, even the strip malls cropping up along the highway, seem suffused with magic. As I watch Sasquatch country slowly give way to sprawl, I think about what Paula Kirk said: we can only ever see something if we look at it. We earn our encounters with the world by paying attention. As I leave the BCSCC behind, John Kirk tells me to write honestly about what I learned today. He believes cryptozoology needs this. “Tell the truth,” he says. That is, after all, what he’s trying to do. The only place where Sasquatch definitely exists, and won’t be chased away, is in the human imagination. The monster’s grip on our culture (the powerful grip of a twelve-inch-long hand, if cryptozoologists are right) reveals a deep ambivalence about how we see both the world we live in, and ourselves. Are we masters of nature, or utterly subject to it? As we encroach further and further into places once counted as wild, our need to believe in the earth’s undiscovered enclaves grows more pressing. We go looking in order to assure ourselves that there’s still something left to find.

The Sasquatch is a wild man; us, but also not-us. It offers fodder for an ancient and tenacious crisis of human identity: capable of acting enlightened as gods, we are stuck in our mortal bodies, doomed to live as animals. Sasquatch—our dumber, more powerful, more beastly cousin—looms between what we fantasize we could be, and what we fear we are. “I sense that there’s the possibility for a kind of post-cryptid cryptozoology, for a more serious, less adversarial conversation between cryptozoologists, skeptics and academics about monsters,” Loxton tells me. “Monsters are more valuable than just the question of their physical existence: there’s something there that tells us something about us. It is part of the fabric of our culture to talk about monsters, and to wonder about the things that lurk in the darkness. I think that these are ideas worth pursuing, even in a world that has a complete absence of actual, living cryptids.”

As Steenburg puts it, “This is probably one of the last great mysteries of the Canadian frontier—or the North American frontier, for that matter. Does this animal exist or doesn’t it?” How would he feel if the Sasquatch was proven not to exist? “I’d feel I’d done my part to record a great piece of Canadian mythology,” he says. “When you solve a mystery, if you reach a conclusion you weren’t hoping for, that doesn’t make it any less solved.”

In over thirty-five years of pursuit, Steenburg has only had one possible Sasquatch sighting of his own. In 2002, he was driving on the west side of Harrison Lake when far away, at the top of a hill, he saw something pass through the gap in the trees where a power-line cut through the woods. Whatever it was appeared quickly, and disappeared faster. All Steenburg will attest to is that he saw something big, black and walking upright. “My basic philosophy is: stick to the facts, and never deviate from the facts,” he recites. (Apparently this philosophy is well-known: later, one of his fellow investigators strikes a pose and repeats the catchphrase, brandishing an imaginary pipe.) The possibility that it was a very large man walking where no man should have been, or the possibility that it was a Sasquatch, are both speculation. “If that was a Sasquatch, I’ve seen one; if it wasn’t, I still have not.”

Steenburg spends a lot of time interviewing eye-witnesses. He keeps his bullshit detector on high alert for both hoaxes and innocent mistakes. “To be a good researcher you have to have a healthy dose of skepticism. You have to be willing to admit you may be wrong. Because if you can’t, you’re not really a researcher: you’re an advocate. Most so-called researchers act like ministers pushing a faith. This is not about faith.” Steenburg cuts himself off mid-sentence and points down the swampy creek we’re standing beside. At the end of our line of sight, two dark shapes hover where the reeds blend into the forest. “See that there? Doesn’t that look strange?” he asks, sounding a little strangled. And he’s right—following his finger across the water, the darkness morphs into something more substantial, and for a moment, I can see a figure retreating into the woods. “I’ll tell you what that is,” Steenburg says, his voice suddenly clear and certain. “Those are shadows, logs, and bushes.”