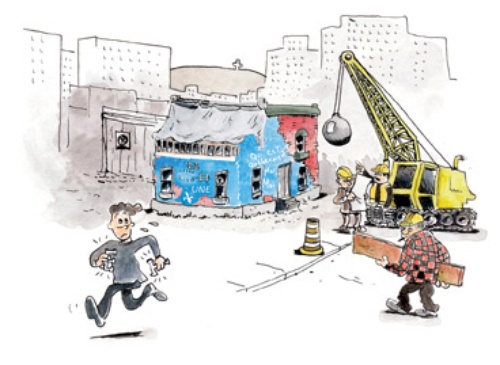

Illustration by Michel Hellman

Illustration by Michel Hellman

Letter From Montreal: Il Et It Une

Only four snippets of text remain, part of a lengthier phrase broken up by time and neglect.

The building at the corner of my block is a mild curiosity. It is a two-storey brick structure, typical of this neighbourhood, although its alley side is painted sky blue. The building has been boarded up for the three years I’ve lived here on Édouard-Charles Street, and the paint in the alley is peeling off, the blue now complemented by the muddy red of the brick beneath.

More intriguing, however, are a number of wood-block letters, white but faded, hung like clouds against the blue bricks. Whatever their message was, it is now incomprehensible. Only four snippets of text remain, part of a lengthier phrase broken up by time and neglect: “IL ET IT UNE.”

It is French, of course. The letters are capitalized and relatively small—roughly six inches tall and one inch thick—with exaggerated serifs. (The typeface is similar to Clarendon, according to a friend’s mobile app.) The “UNE” suffered an unknown fate, and has been replaced with sloppy, spray-painted letters.

“IL ET IT UNE”—what does it mean? I walk by that broken collection of conjunctions, pronouns and articles nearly every day, and the question niggles at the back of my mind. Beneath the letters someone has painted a white fleur-de-lys, a potent nationalist symbol; four such flowers appear on the blue Quebec flag. Could the building’s façade have served as a stand-in flag? Is “IL ET IT UNE” all that remains of a sovereigntist slogan?

I have begun to ask these questions with more urgency, because the building is about to be torn down—and because “IL ET IT UNE” has suffered recent damage. Earlier in the year, while the adjacent building was being gutted and refashioned into condos, construction crews bashed their way about and inadvertently destroyed several of the letters. All that remains is “IL ET” (and, of course, the spray-painted “UNE”).

And so, as a new construction crew moves in, I decide to take action. Late one evening, in an act of vandalism-cum-conservation, I go into the alley and pry off the “I,” the “E” and the “T” (the “L” is already damaged beyond repair). Then I take to the internet. First, on Facebook, I post an image of the wall and the three letters I’ve rescued, asking if anyone recognizes the mysterious phrase. Soon I have a response. “Il était une fois,” a friend replies: Once upon a time.

What does this mean? On a web forum, I find a useful five-year-old discussion. The corner building, apparently, was once a children’s shop, selling either toys or clothes. The shop was called Il était un petit navire—There once was a little ship—after the title of a popular children’s song.

Now “Once upon a time” makes sense. But what about the fleur-de-lys? On Flickr, I find an earlier image of the street side of the building. It, too, had been painted blue at the time, and was decorated with a splash of politically charged graffiti. “Qui est Québécois?” someone had asked—Who is a Quebecer? Someone else responded: “Moi.” And someone else: “Moi.” In the mid-nineties, with the sovereigntist movement at its height and the 1995 referendum looming, a building painted the same blue as the flag would have been an obvious target. The fleur-de-lys in the alley, I realize, belonged to this exchange.

The building at the corner of my block is a former children’s shop, yes. An abandoned, graffitied ruin—that, too. But it is also a canvas on which, over the years, the community painted its innocence, its politics and its hope. A true urban palimpsest.

Now that I know why the letters were there and what they once said, I regret their demise even more. There is a phrase common in Quebec: “Je me souviens”—I remember. Inasmuch as I can participate in this sentiment, I will hold on to my three rescued letters—a reminder of the history of my neighbourhood, and of the deeper connection I can have with it simply by looking around.